Marshall McLuhan at John Hopkins University.

Media

BEST MOVIES OF THE YEAR

Such lists make no sense, and we all know it. For one thing, only the films made with guaranteed distribution deals — fewer and fewer, these days — are released in theaters the same year they have their "premiere" at a film festival. If I saw a film at a festival this year but it isn't in a theater in my city until next year, when did it "come out"?

Secondly, films come out in theaters and on DVD months or even years apart depending on where in the world you live. A few years ago, New Yorkers, Londoners and Parisians could imagine they had seen just about every film in the theater that was worth seeing, and cinephiles in Hong Kong could procure a DVD of just about any film as soon as the filmmaker had burnt a copy for a festival — but this is also rapidly becoming a thing of the past. The only chance anyone has of seeing the bulk of the most interesting, innovative and important films in a given year would be to globe-trot from Venice to Cannes to Toronto to Sundance to Edinburgh to Rotterdam to Tokyo to Thessaloniki to Ann Harbor, ad infinitum.

These facts make any list of the "best films of the year" highly suspect, because it takes either a genuinely or willfully ignorant person to believe they have had a chance to see all of the likely contenders — let alone be surprised by a first-time filmmaker or experimental work. Most people's best-of lists look like an advertisement for their local megaplex, fully accepting and promoting the pretense that the studios and cinema corporations are going to serve up the coincidentally most important and most profitable films of the year in global cinema. At the very least, these lists should come with a lengthy introduction of acknowledged biases and shortcomings — to not do so is at best misleading and indecent, at worst ethnocentric and damaging to the struggle of independent filmmakers to have their films seen. Slightly less idiotic but still outrageous are the claims that any given year was "a bad year for movies" — which operates under the same pretense that the best films were the ones that had the movie stars, the huge budgets or the theatrical distribution in say, Los Angeles.

My generation seems to be far more enlightened and mature about their music than their films. I have never seen a friend or a reputable magazine claim that the Grammy's represented the best albums of the year, or that all one had to do was tune into their local corporate pop radio station during their commute in order to be exposed to the best that the music world has to offer. In both cases, most adults I know seem to distinguish between "popular culture" and the rest of it — but in the case of film, a lot of people I know and many contributors to cultural discourse that I come across make little or no effort to seek out the non-commercial, the international, the independent and the original. In short, I don't know many people who would say with a straight face that the latest Beyoncé record represents the finest achievement in the art of music this year, yet I am inundated with similar claims for Black Swan, Toy Story 3, The Fighter, etc.

I find it useful to think about the differences between the way we speak about film and the way we speak about any other art form, as it betrays the extreme value and burden that is placed upon moving images as the official conduit of mass culture. If anything, film is discussed in similar terms to literature — we have our genres, our light fare, our masterpieces, our classics, our gender-specific categories. What we don't have in literature, however, is the commonplace serious assertion that John Grisham's The Confession was the most noteworthy and finely written novel produced anywhere in the world in 2010. While we are happy to describe such books as guilty pleasures, we stop short of giving them the ultimate praise for their "entertainment value", and yet in film, there is a pressure to only consider a film as great if it was able to "entertain" us.

We do not ask our paintings to "entertain" us, nor our sculptures or other fine arts, and this is perhaps due to some strict ordering of our experiences of all things "narrative". More sinisterly, and accurately I fear, it is clear that "entertainment" is an extremely loaded term — one which carries with it the desire to see reflected back at us our own supposed desires, fetishes and foibles. We want to see the film that everyone else has seen, that has made an obscene amount of money or cost an obscene amount of money to produce, the one which titillates us with it's giddy fetishizations of women's bodies, in part, I believe, because we seek an experience that is essentially masochistic. This is the success of the culture industry: to have replaced our desire for emancipatory, ecstatic, beautiful and meaningful cultural experiences with a matter-of-fact hopelessness — that "good film" is either boring, too difficult, or simply a pretentious fallacy — which is gratified with increasingly exaggerated and distorted representations of violence, meaninglessness, fear and bigotry.

I can't blame people who have no time or access to find the thousands of truly beautiful, enjoyable, and important films made around the world every year because their stores, their cinemas, their reviewers and their friends make no mention of them. I haven't been able to see many of the films that have played around the world this year that I would want to see. I do, however, blame reviewers. They have a clear choice — to pretend along with the studios that the films that win at Cannes are in fact to boring to be enjoyed by "normal" people, or to actually do their homework and attempt to look at the culture of their time in a historical and economic context.

I also take our Facebook, twitter, blog and forum reviews seriously as non-professionals since we all know that such opinions have a greater and greater aggregate effect all the time in relation to the official reviews and awards. Let's acknowledge that we haven't been able to see the best films of the year because they were under-funded, censored, unrecognized and hidden from us. Let's acknowledge that we have been lazy about finding them and supporting them. Maybe then we will get pissed off enough to change this sorry, sorry state of affairs.

DROP THE I-WORD

Drop the I-Word is a campaign to expose the racist impacts of referring to immigrants as "illegals." This i-word is a damaging term that divides and dehumanizes communities and is used to discriminate against immigrants and people of color. The i-word is shorthand for illegal alien, illegal immigrant and other harmful racially charged terms. The campaign’s goal is to eliminate this terminology from popular usage and public discourse. Visit droptheiword.com to learn more and take the pledge.

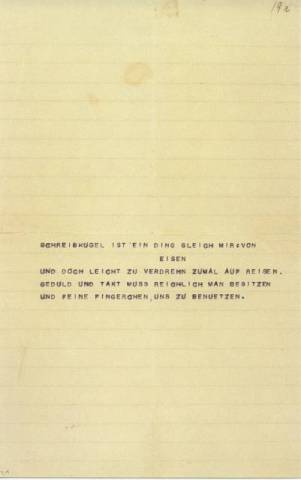

Nietzsche's Typewriter

THE WRITING BALL IS A THING LIKE ME: MADE OF IRON

YET EASILY TWISTED ON JOURNEYS.

PATIENCE AND TACT ARE REQUIRED IN ABUNDANCE

AS WELL AS FINE FINGERS TO USE US."

— Friedrich Nietzsche, on February 16th 1882

Praising with Faint Damnation: the Critical Response to "Inglourious Basterds"

(This entry is reposted from my old blog, Decorporation Notes - September 7th, 2009.)

I’m afraid that in the admirable quest for a subject of cinematic criticism, we’ve settled instead on a suitable subject for the criticism of mass spectacle.

The conspicuous success and consumption of Tarantino’s media events is certainly worth discussing, but to do so in terms of cinematic intent is like discussing the acting technique of a ventriloquist’s dummy: Tarantino has succeeded in pantomiming meaning with enough unconsciousness to suspend the audience’s and critic’s disbelief long enough for them to believe they are watching a film — but so, for that matter, did WALL-E. If we actually believe a single frame of Tarantino to be intentional, where, then, were the moral debates over his use of Samurai history in Kill Bill? The attention drawn to the very difficult lives of real undercover law enforcement agents following the release of Reservoir Dogs?

The impersonation of cinemaWhat better way to attract critical attention that to convincingly pantomime the film genre that is ostensibly concerned with the greatest moral problems of humanity? In terms of cinema, I believe the equation in Inglourious Basterds is boringly simple: Tarantino has merely shifted his aspirations in the decidedly horizontal spectrum of establishment positions — and he is celebrated winkingly for his un-self-conscious ability to regurgitate formulas of dialog, plot, camera movement and montage, and, of course, his complete lack of any compunction towards the deepest cynicisms of his age

The impersonation of cinemaWhat better way to attract critical attention that to convincingly pantomime the film genre that is ostensibly concerned with the greatest moral problems of humanity? In terms of cinema, I believe the equation in Inglourious Basterds is boringly simple: Tarantino has merely shifted his aspirations in the decidedly horizontal spectrum of establishment positions — and he is celebrated winkingly for his un-self-conscious ability to regurgitate formulas of dialog, plot, camera movement and montage, and, of course, his complete lack of any compunction towards the deepest cynicisms of his age

It is fascile to analyze the events of the funding, production, distribution, marketing and mass viewing of this strip of celluloid without bringing to bear the economic and social mechanisms that allow for such things to happen, and which profit by them. And in this regard, to single out this film for critique on the basis of it’s historical content is to believe that the filmmakers, actors, cinematographers, art directors et cetera actually meant “Nazi” when they uttered the word, made the costume, or wrote the press release. The so-called “inversion” or “rewriting” of history in the plot might be worth discussing if the filmmakers were intending or even capable of referencing reality instead of titilating themselves and the audience with their willingness to destroy understanding and meaning through their reflexive reflexivity. Reviewers may wish to discuss the “fantasy” of Jewish people taking revenge on living Nazis — going along, as it were, with the joke: the Nazis and Jews being pantomimed here could be replaced with any aggressors and victims of historical incident, granted that the history is still politically or emotionally charged enough to illicit post-ironic glee in its dismissal as a purely rhetorical device.

The real fantasy, I feel the need to quip, is the idea of audiences encountering a film in the cinema that actually deals with the moral, ethical, political or emotional problematics of the Jewish (or any other) genocide and its representation. Of course, such fantastic films are very real, just not commonly given value or representation in the mass media. In avoiding the discussion of such films, I can only conclude that reviewers are skirting the much more complex matter (not reducible to upturned thumbs or a star-based quantification scheme) of why and how certain objects of mass spectacle arise, are given pseudo-critical attention, and praised with faint damnation.

Therefore (surely you saw this coming) the most glaring oversight in any discussion of Inglourious Basterds is the figure of Jean-Luc Godard, recognized as the filmmaker most preoccupied with the holocaust — presumably because to enter into the complex cinematic significance of the Histoire(s) or In Praise of Love would be to remove the irresistible shininess of the glare of mass spectacle from this slight, pathetic and barely-willed piece of fake-blood-strewn shit Tarantino has most recently withered from his hyperactive anus. I shivered as I saw once again, the words “A BAND APART” appear at the beginning of Basterds, and was reminded of the quote by Godard, “Tarantino named his production company after one of my films. He would have done better to give me some money.”

Here are some more fantasies: perhaps the budget of Basterds should have gone towards the American broadcast or distribution of the Histoire(s). The thesis of Godard’s Histoire(s), it has been many times said, is that the history of film, and in some extension, mass media, has been forever changed by it’s failure to show the atrocities of the camps while they were operating. I am tempted to give Tarantino the credit of reinvigorating this failure for a generation who is already ignorant of it’s historical antecedents (filmic and moral) — but again, I would still be participating in the pantomime. The primary moral dilemmas on display in the theater on the night I saw Basterds concerned the valuation of art in America.

Pop formalism being the order of the day — fascinating critics and mass audiences alike — we can all masochistically applaud the death of film culture presented to us in the beige, recycled composites of the International New Waves via the American “Mavericks” (There Will Be Blood, No Country for Old Men) or the callous (and sometimes bigoted) reduction of social allegory to an easily subvertible, vapid genre technique (Slumdog Millionaire, District 9). In this climate, I see very little to be remarked upon in Basterds as a film, or Tarantino as a filmmaker — the “self-reflexivity” and “genre-blending” he utilizes is as remarkable as his use of color film or sound. Why, however, we believe that it is to be considered a film at all — a discrete object of culture — is worth discussing. And in that discussion, perhaps his faint damnation of war criminals could be adequately reviled.

Let the Media Die

One need not spend much time watching or reading the news these days to find discussions regarding the unsustainablility and seeming collapse of traditional economic models of news production and dissemination — every major print, radio or television outlet has, with varying degrees of reflection and superficiality, addressed the subject many times. The premise, one can surmise, of most of these discussions is that we have all been benefited greatly and unambiguously by the models that existed throughout the 20th century in Western countries — government subsidized, commercial and corporate institutions that were able to research, investigate and produce vital news and debate and disseminate it for public consumption largely through advertising revenue.

Tune into the BBC, NPR, or pick up a copy of Wired, and you will find, on the one hand, this era described in golden nostalgic tones, and the figure of the down-trodden, old-school “pen and paper” journalist warning us all against the looming “chaos”, “wild west” and “free-for-all” of a predominantly internet-based news model. On the other hand, you will find the gleeful optimist describing the potential advantages to news and media organizations if they can only catch up to the times and develop ways to profit from the overall greater interest and potential value of such a voracious audience as the billion-strong internet citizenry. You will hear concepts proposed such as the hybrid free/paid service, where a certain amount of content is provided free, but the rest is available only for subscription; or the forced advertising that has already gained traction on commercial sites, whereby the user must first view a video or advertisement before being led to the content they are searching for. At the fringe, you may even encounter “radical new theories” such as the “attention economy” — wherein you, the consumer, are trading your attention for information.

There is a parallel discussion regarding the entire internet economy that involves developing strategies for generating profits for such widely used tools as search engines, wikis and social-networking sites. From the point of view of the developers, share-holders and investors of such services, they are providing a valuable way to access, store and organize a vast po0l of user generated content. For many of these companies, the services they have designed are fulfilling demands which did not previously exist. What is making media corporations and journalists very nervous is the gap in revenue being generated by the new internet-based platforms and the enormous print and television advertising profits of yesteryear. “Where has this money gone?”, they wonder.

What you will not hear in this discussion — what does not occur to commercial media producers — is the idea that media should be publicly generated and distributed. Just as the natural resources of nations are increasingly privatized, so too are information channels. Due to their extremely expensive technical apparatus, television, radio, and even print formats were easily controlled by vested interests. The airwaves, though nominally public, have been leased in perpetuity to those with the largest signals — honor boxes and journalist access only granted to those with the largest presses. The relatively widespread access to production technology of internet-based media is truly problematic for all those who thrive within this hierarchy.

I would like to propose a solution: the death of mass media. This is, I feel, the only solution to the real looming threat: on the pretense of genuine concerns for access to reliable and penetrating news information and analysis, media conglomerates will be allowed to further commercialize and control the information economy. The internet itself has, from its inception, lost this battle — the struggle for universal access and the concept of media sources as public utilities have found little purchase in the “start-up” driven implementation of networks and services. And yet, even if that obstacle is overcome, the models of pay-per-view, subscription, or copyright-protected news content have the very real potential of pricing-out millions of internet users who seek to find and produce information vital to their ability to be active members of democratic political systems.

This can be seen as a pivotal moment in the development of state-supported capitalism, and thus, a crucial battleground for social justice. The current models being explored are exploiting the fact that people who have the quality of life sufficient to use the internet actively are producing enormous, unprecedented amounts of information, which in their model, is potential value. If we choose to ignore and debase this massive source of human knowledge as completely “unreliable” because it lacks the publishers and executives to determine its techniques and methodologies, we are losing sight of any notion of progress in public literacy and eduction. The accuracy, reliability and usefulness of publicly and freely produced news and media on the internet depends upon our commitment to extending access to education and information as a basic human right. If we allow our public information channels to be dominated by fewer and fewer bastions of the commercial media system, our hopes for maintaining a vibrant and emancipatory information ecology are futile. The development of a useful and valuable publicly accessible mediasphere is absent in the mainstream media’s discussion of future news models precisely because the ideas of universal human rights and the struggle for equitable standards of living on which such a development depends are unthinkable in their capitalistic worldview. If the topic of publicly owned media is ever breached, it is demonized through the examples of state-controlled media in repressive “Socialist” and “Communist” regimes.

How can internet-based news somehow be immune to the corrupting potential of power? The latent emancipatory potential in the internet (if, and only if universal access can be successfully pursued) is perhaps found in the unique nature of the hardware/software divide, a technological formulation that can be fitted to almost any political structure — even radical ones. If we can prioritize and demand the universal development of a broadband infrastructure (hardware) as a publicly owned and guaranteed utility, the means of production (software) of digital media content can be multiplied, modified, utilized and developed ad infinitum. In a truly neutral “net”, the inequities of hardware-based industrial print and wireless transmission radio transmission do not exist. It is not, in this respect, a coincidence that the Internet Mapping Project has generated images of the global digital network that resemble organic and neural structures more than a little.